In this edition:

When to measure and when not to measure

How algorithms are rewriting the history of indie rock

WHO runs the world? Marianna Mazzucato runs the world!

But first:

🎙️

Starting this week, Weekly Bento events will be hosted by community facilitators.

Community Facilitators are people who started out as attendees, went deeper in Bento Groups, and are now helping to create spaces too. Thanks so much to the wonderful Evan, Flo, and Yuki for agreeing to lead the first one! Join us here:

Weekly Bento

Sunday Nov 22

12pm EST

RSVP

🙋

When to measure and when not to measure

During last week’s Town Hall there was a great debate in chat and during the Q&A about the importance of measurement. The Bento Society sees measurement and data as core to its theory of change but there’s reason to be skeptical of always resorting to it. Some things shouldn’t be measured. Measurement can be a way of avoid more difficult conversations.

These are fantastic questions that I’d love to have a deeper discussion about. In the new year, I’m going to host a special Bento experimental forum for us to go deep into this question. If there are people in the Bento Society or connected to us who have relevant experience or interest in this question, it would be great to hear from them.

Share your info here to be part of it.

📰

Why is the obscure B-side “Harness Your Hopes” Pavement’s Top Song on Spotify? It’s Complicated by Nate Rogers (Stereogum)

Speaking as a longtime music critic who crafted the definitive list of the Top 20 Pavements Songs of All Time, this story about why Spotify’s top songs for artists like Pavement contain completely bizarre anomalies is fascinating. It’s all about the algorithm:

The musician and writer [Damon Krukowski] was fascinated with the question of how “Strange” became his former band Galaxie 500’s top Spotify track — by a significant margin — even though it was not a single, was never particularly popular in the past, and wasn’t being picked up on any prominent playlists. In June of 2018, Krukowski laid out the conundrum on his blog, and soon he received a possible explanation from a Spotify employee.

Glenn McDonald, who holds the title of “data alchemist” at Spotify, had taken an interest in the case, and decided to look into it. What he found is that the sudden jump in plays for “Strange” began in January of 2017, which was “the same time Spotify switched the ‘Autoplay’ preset in every listener’s preference panel from off, to on,” as Krukowski recounted on a follow-up blog post. McDonald explained to Krukowski that the Autoplay feature actually cues up music that “resembles” what you’ve just been listening to, based on a series of sonic signifiers too complex to describe. In this case, “Strange” had been algorithmically determined to sound similar to a lot of other music, and was frequently being Autoplayed to the point that it took on a life of its own, and eventually eclipsed the band’s other tracks. It continues to do so to this day.

What’s valuable about a song in 2020 isn’t that it’s popular, it’s that it’s algorithmically similar to other things that are popular. Entire new value sets that connect the things around us are reordering the world in strange ways. In the future, actual ‘80s teen movies will compete with Stranger Things to be the more canonical depiction of the decade. The cultural canon of the past competes against an unknown future (and unknown algorithms) constantly mining and rewriting the rules of relevance.

🤓

“Is This Profitable?” By Elena Burger

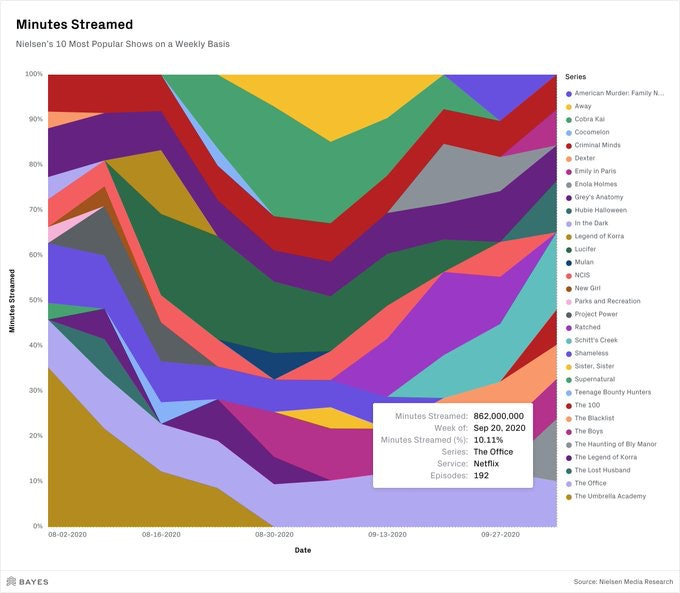

This smart essay goes deep into time as the most desired form of capital in the world of entertainment. After drawing on fascinating data tracking the millions of minutes spent watching various streaming services each week (pictured above and explained in more depth in her piece), author Elena Burger writes:

You might look at the charts above wonder — how do these “millions of minutes watched” convert into viewers? Nielsen tracks minutes, not people. This, in itself, is kind of a perfect encapsulation of the present moment. Time, not people, as the end-state of all measurement.In the world of analogue television and in film, producers are (or were) rewarded for outsize successes, either in the form of syndication fees (e.g. when you license your show after it hits 100 episodes) or in film financing where producers share in a movie’s profit. Those fees and profits usually have some kind of relationship to the number of viewers a show or film has. But in streaming, financial upside for production is usually capped (though some regions are trying to change this; Netflix, for example, just struck an agreement with German creators to pay out royalties for shows filmed in the region).

Netflix is comfortable operating at slimmer margins than networks and film studios did in their heyday, which is why they’ve been able to out-spend their rivals (who had gotten perhaps lazily accustomed to affiliate fees and ad revenues). Investors don’t care that Netflix operates at roughly 20% EBITDA margins, while most cable companies are around double that at ~30-40%…because the idea is that Netflix can outspend competitors, and doesn’t have to disentangle themselves from the affiliate fee/advertising-based model of legacy cable companies (that’s the very short version…the longer version is the hyperlink in the first sentence of this paragraph).

This means that winning, for Netflix, is less a matter of higher profits than it is a matter of triumphing in the realm of time, and how you personally choose to allocate it. While this has led to some good things (more shows means more opportunities for creatives), it also has led, I think (and I think a lot of other people think too), to an over-saturation of content.

Two lines stand out: “time, not people, as the end-state of all measurement” and “winning, for Netflix, is less a matter of higher profits than it is a matter of triumphing in the realm of time, and how you personally choose to allocate it.” Subscribe to Elena’s newsletter here.

🔥

From the press release:

“The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the consequences of chronic under-investment in public health. But we don’t just need more investment; we must also rethink how we value health,” said WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus

Chaired by noted economist Professor Mariana Mazzucato, Professor of the Economics of Innovation and Public Value and Founding Director in the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose at University College London, the Council will aim to create a body of work that sees investment in local and global health systems as an investment in the future, not as a short-term cost. Designing such investments makes our economies more healthy, inclusive and sustainable.

“The time has come for a new narrative that sees health not as a cost, but an investment that is the foundation of productive, resilient and stable economies,” Dr Tedros said.

We highly endorse Mazzucato’s work. The fact that she’s one of the 100 most influential people in the world right now is a very good thing. Congrats Mariana on your 76th new gig just this year!

🕸️

Trust and Doubt in Public-Sector Data Infrastructures (Data and Society)

One of our favorite people in the world of data is the trailblazing danah boyd, Founder and President of the very excellent research organization Data & Society (perhaps a subconscious inspiration for the Bento Society?). They’ve announced a spring symposium on Trust and Doubt in Public-Sector Data Infrastructures, a topic very much in line with our recent discussion of egalitarian data.

Apply or put an eye on it here.

🤐

How did you enjoy this edition of The Bento Society? How could it be better? Your feedback is appreciated.

Peace and love,

Yancey Strickler

The Bento Society